A Practical Guide to Modern Data Warehouse Modeling

TL;DR: Key Takeaways

- Modeling Philosophies: Choose the right approach for your goals: Kimball for speed and BI usability, Inmon for a central single source of truth, or Data Vault for agility and auditability.

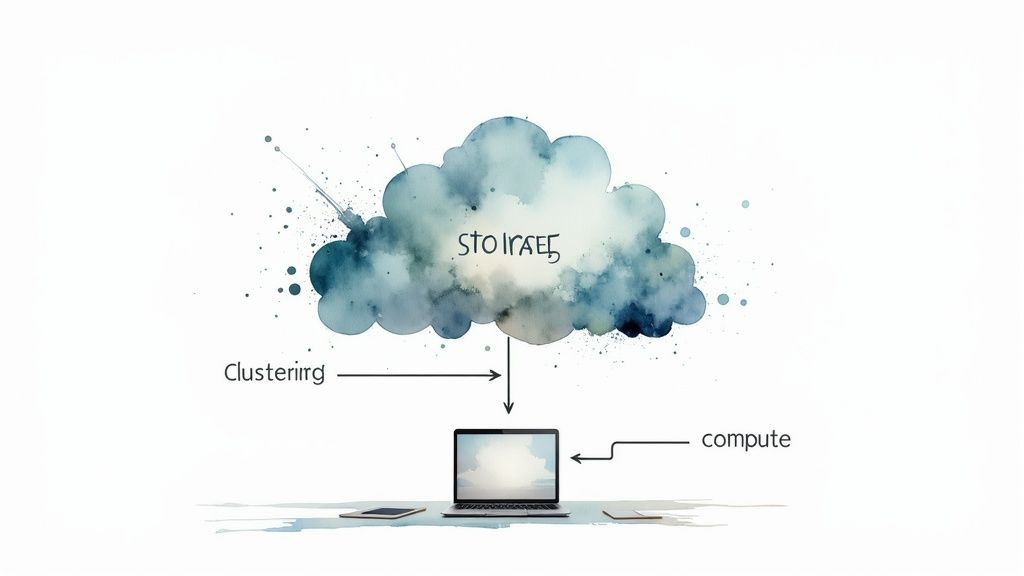

- Cloud Architecture Shift: Modern cloud platforms (Snowflake, Databricks) separate storage and compute, making Star Schemas and wide, denormalized tables the gold standard for performance.

- ETL to ELT: The paradigm has shifted to ELT (Extract, Load, Transform), allowing raw data to be loaded first and transformed later, increasing flexibility and enabling schema-on-read.

- Performance vs. Storage: In the cloud, optimize for query speed (compute costs) rather than storage space. Use partitioning and clustering instead of strict normalization.

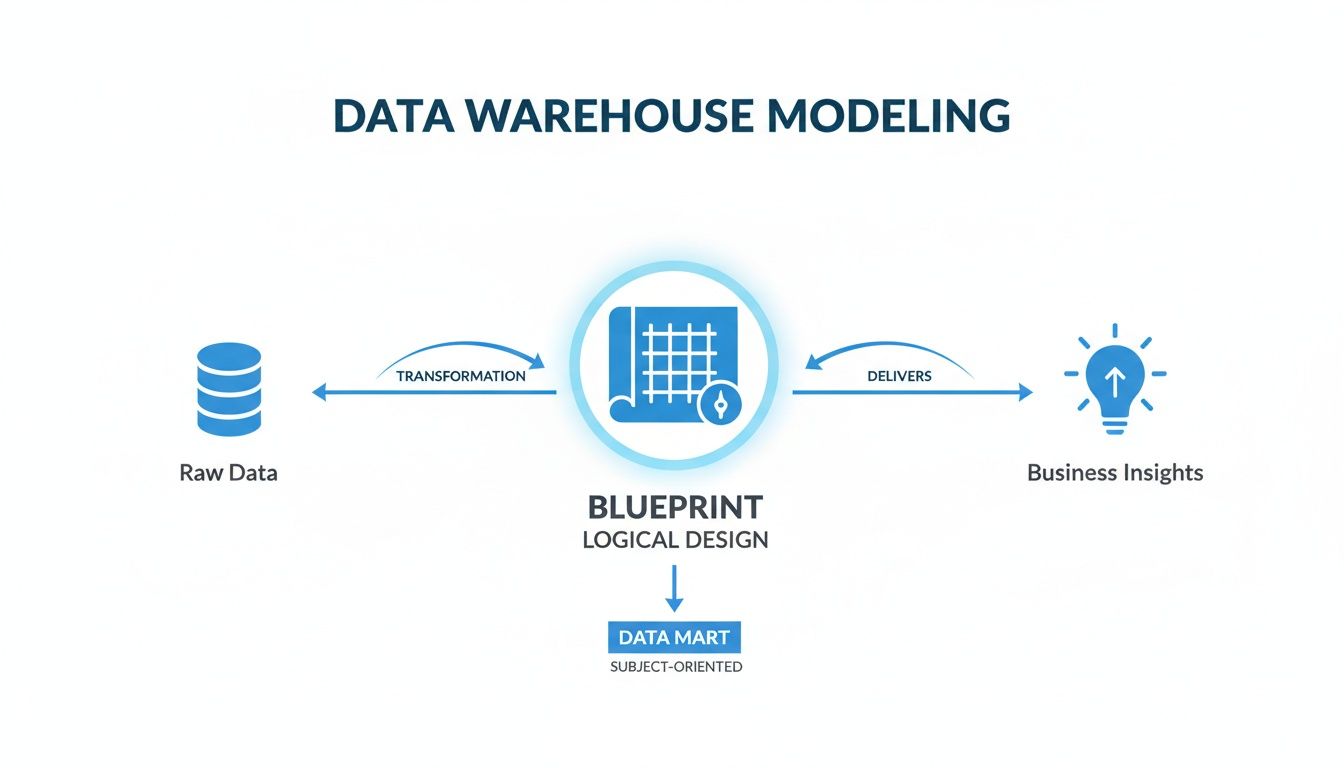

Data warehouse modeling is the architectural process of structuring raw data for analysis and business intelligence. It’s not about storage; it’s about intentional design. Without a coherent model, you have a data swamp—a repository of unusable information. With a solid model, you have a foundation for reliable, high-performance analytics.

Why Your Data Warehouse Model Is Your Most Critical Asset

A data warehouse model is the blueprint for your analytical systems. A flawed blueprint guarantees a flawed structure, leading to common data problems: slow queries, inconsistent reports, and a general lack of trust in the data.

The objective of data modeling is to translate complex business processes into a logical, query-friendly structure. It enables a non-technical user to ask, “What were our product sales in the Northeast region last quarter?” and receive a fast, accurate answer.

From On-Premise Rigidity to Cloud Flexibility

Historically, data warehouse modeling was constrained by the limitations of on-premise hardware. Expensive storage and finite compute power mandated highly normalized models to conserve space.

Today, this paradigm is obsolete. Modern cloud platforms like Snowflake and Databricks have decoupled storage from compute, making both resources effectively elastic and affordable. This fundamental shift has changed modeling priorities from conserving disk space to optimizing query performance and ensuring architectural flexibility. This evolution fuels significant market growth—the data warehousing market, valued at $33.76 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $69.64 billion by 2029. For a detailed analysis, see these data warehouse market trends. Modern cloud modeling techniques are essential for managing this data growth and extracting value.

A data model is the crucial link between business logic and the technical systems that support it. A correct model provides a stable foundation for analytics; an incorrect one is built on quicksand.

Ultimately, a data model is more than a technical diagram. It is the core of a data strategy, enabling everything from standard reporting to advanced analytics and machine learning. A well-designed model minimizes costly rework and provides the organization with data it can trust for decision-making.

Choosing Your Modeling Philosophy: Kimball vs. Inmon vs. Data Vault

Selecting a modeling philosophy is a foundational architectural decision. It dictates the ease of data access for analysts, the system’s adaptability to business changes, and the overall trust in the data. The decision determines whether you are building for immediate, specific use cases or for long-term, enterprise-wide consistency.

The discussion centers on three primary methodologies: Kimball, Inmon, and Data Vault. Each offers a different blueprint for organizing data. The optimal choice depends on organizational priorities: is the primary driver speed-to-insight, a single source of enterprise truth, or the ability to adapt to a constant influx of new data sources?

The answer is context-dependent.

This diagram visualizes the process. Modeling is the critical intermediate step that transforms raw, unstructured data into a logical framework, creating a blueprint for generating business insights.

Without this intentional design, you’re just hoarding data. With it, you’re building a powerful analytical engine.

The Kimball Approach: Optimized for Speed and Usability

Developed by Ralph Kimball, dimensional modeling is arguably the most prevalent approach in practice. Its primary objective is to make data easy for business users to comprehend and fast to query. The focus is on delivering answers quickly.

The methodology is analogous to organizing a retail store into subject-specific departments: Sales, Marketing, Inventory. These are data marts. Each mart is a self-contained unit holding all relevant information for a specific business process, typically organized in a star schema.

To achieve this speed, the Kimball model intentionally denormalizes data, meaning some information is duplicated. While this contradicts traditional database normalization principles, it is a pragmatic trade-off. It drastically reduces the number of table joins required to answer analytical questions, resulting in dashboards and reports that load in seconds instead of minutes.

- Key Strength: Unbeatable query performance and a user-friendly structure optimized for business intelligence.

- Ideal Use Case: Teams that must deliver business-facing analytics rapidly. It empowers departments with the data they need to manage their operations effectively.

- Practical Trade-off: Without disciplined governance, the focus on separate data marts can lead to data silos, creating discrepancies between a “sales version of the truth” and a “finance version of the truth.”

The Inmon Approach: Built for a Single Source of Truth

In contrast to Kimball’s bottom-up approach, Bill Inmon advocates a top-down philosophy. The primary goal is to establish a single, centralized, highly normalized Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW). This EDW serves as the definitive single source of truth for the entire organization.

The core of the Inmon model is a data repository structured like a traditional transactional database. By enforcing strict normalization (typically Third Normal Form), it eliminates data redundancy and ensures enterprise-wide consistency. After this central hub is established, smaller, department-specific data marts are derived from it for analytical use—these marts often adopt Kimball’s dimensional structure.

The fundamental difference is the starting point. Kimball builds the data marts first and integrates them later. Inmon builds the integrated warehouse first and creates data marts from it.

This methodology requires significant upfront planning and complex ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) processes to populate the normalized central warehouse. The reward for this initial investment is robust data integrity and consistency that scales across the enterprise.

The Data Vault Approach: Designed for Agility and Auditability

Data Vault is a more recent methodology, developed to address the challenges of the big data era. It is engineered to handle large data volumes from numerous disparate sources while maintaining flexibility and providing full auditability. It is a hybrid model that incorporates principles from both Inmon and Kimball.

The model is constructed from three core components:

- Hubs: These store unique business keys, such as CustomerID or ProductSKU, representing core business entities.

- Links: These define the relationships between Hubs (e.g., a link connecting a customer to a product they purchased).

- Satellites: These store all descriptive attributes related to the Hubs and, critically, track the history of all changes to that data over time.

This modular design is Data Vault’s primary advantage. Adding a new data source involves creating new Hubs, Links, or Satellites without re-engineering the existing core structure. This makes the model highly adaptable and scalable.

Furthermore, it captures raw data upon arrival and meticulously tracks every subsequent change, creating a fully auditable historical record. This is a critical feature for regulatory compliance and data governance. The architecture is also well-suited to modern ELT (Extract, Load, Transform) patterns, where raw data is loaded first and transformations are applied later.

Kimball vs. Inmon vs. Data Vault At a Glance

This table provides a concise comparison of the core principles of each methodology.

| Attribute | Kimball (Dimensional) | Inmon (Normalized) | Data Vault (Hybrid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Bottom-up: Build business-focused data marts first, then integrate. | Top-down: Build a central, integrated warehouse first, then create data marts. | Hybrid: Load raw, integrated data first, then model for business needs. |

| Primary Goal | Speed-to-insight and business user usability. | Enterprise-wide data consistency and a single source of truth. | Scalability, agility, and historical auditability. |

| Data Structure | Denormalized (star/snowflake schema) for fast queries. | Normalized (3NF) to eliminate data redundancy. | Raw data in Hubs, Links, and Satellites to track history. |

| Best For | Departmental BI, rapid prototyping, teams needing quick analytical wins. | Large enterprises requiring strong data governance and a stable, central repository. | Environments with many data sources, evolving requirements, and strong compliance needs. |

| ETL/ELT Pattern | Tends to favor ETL, as transformations are defined for each mart. | Heavily reliant on complex ETL to populate the normalized warehouse. | Perfectly suited for ELT; load raw data first, transform later. |

The objective is not to declare a single “winner” but to select the methodology that best aligns with an organization’s specific context and goals. A startup might prioritize Kimball’s speed, while a global financial institution would likely require Inmon’s rigor. A fast-growing tech company integrating dozens of microservices might find Data Vault to be the most practical solution.

Building Schemas That Actually Work

After selecting a modeling philosophy, such as Kimball’s dimensional approach, the next step is to translate theory into a physical database structure. This is accomplished through schemas. In dimensional modeling, the two dominant designs are the star schema and the snowflake schema.

Understanding the trade-offs between these two is critical for building a high-performance and maintainable data warehouse. The choice represents a fundamental balance between query simplicity and storage efficiency, directly impacting query speed and data pipeline complexity.

The Star Schema: Your Go-To for Performance

The star schema is the workhorse of modern business intelligence, designed for one primary purpose: query speed. Its structure is simple and intuitive, consisting of a central fact table connected to multiple dimension tables, resembling a star.

Consider a standard retail sales example:

- Fact Table (

Fact_Sales): This is the core of the schema. It contains the key business metrics—the quantitative measures for analysis, such asOrderQuantity,UnitPrice, andSalesAmount. It also includes foreign keys, likeProductKeyandCustomerKey, that link directly to each dimension. - Dimension Tables (

Dim_Product,Dim_Customer): These tables provide the descriptive context—the “who, what,where, and when”—for the metrics in the fact table. For example,Dim_Productwould contain attributes likeProductName,Category, andBrand. Critically, these dimensions are denormalized, meaning all related attributes are consolidated into a single wide, flat table.

This denormalized structure is the star schema’s main advantage. Because all product, category, and subcategory information resides in the single Dim_Product table, an analyst can filter by brand without executing complex joins across multiple tables. Fewer joins result in faster queries, which is why BI tools and modern cloud platforms are highly optimized for this design.

The core principle of a star schema is to sacrifice a small amount of storage efficiency by duplicating some data to gain a massive improvement in query speed and simplicity.

The Snowflake Schema: Prioritizing Normalization

The snowflake schema extends the star schema by normalizing its dimension tables. Each point of the star is broken down into smaller, related tables, creating a pattern that resembles a snowflake.

Using the retail example, a snowflake design would decompose the Dim_Product table:

Dim_Product: ContainsProductNameand a foreign keySubcategoryKey.Dim_Subcategory: ContainsSubcategoryNameand a foreign keyCategoryKey.Dim_Category: ContainsCategoryName.

The primary benefit is the elimination of data redundancy. The category name “Electronics” is stored only once, not repeated for every product in that category. This saves storage and simplifies updates—a category name change only needs to occur in one record.

However, this structural elegance comes at a performance cost. Answering a query like “What were the total sales for the Electronics category?” requires the database engine to perform multiple joins—from the fact table to the product table, then to the subcategory table, and finally to the category table. These additional joins can significantly slow down query performance, especially on very large datasets.

The Fact Constellation Schema: For Complex Processes

Some analytical scenarios require examining multiple business processes simultaneously. For instance, analyzing both sales and shipping data requires looking at two distinct events that share common contexts. This is the ideal use case for a fact constellation schema, also known as a galaxy schema.

This model is built around multiple fact tables that share one or more dimension tables. For example, a Fact_Sales table and a Fact_Shipping table could both link to shared dimensions like Dim_Date, Dim_Product, and Dim_Customer. This allows analysts to analyze metrics from both processes using the same descriptive attributes, providing a complete, end-to-end view from order placement to final delivery.

Adapting Your Model for Cloud Data Platforms

Data modeling principles established in the on-premise era require re-evaluation in the context of modern cloud data platforms like Snowflake, Google BigQuery, and Databricks. The economics of data warehousing have fundamentally changed, altering the rules for effective modeling.

The key innovation is the separation of storage and compute. This architectural design makes many traditional best practices obsolete.

For years, modeling was constrained by the high cost of disk space, forcing architects to implement highly normalized snowflake schemas to minimize data redundancy. This primary constraint no longer exists; cloud storage is commodity-priced.

The new bottleneck is compute cost. The objective has shifted from saving gigabytes of storage to minimizing the query processing time.

Favor Wide Tables and Star Schemas

Modern cloud platforms are engineered for speed at scale. Their columnar storage engines are highly optimized for scanning massive, wide tables efficiently. As a result, the classic star schema is now the preferred pattern for achieving high performance.

A denormalized star schema uses fewer, wider tables, which drastically reduces the number of complex joins needed to answer a query. Fewer joins mean less compute, faster queries, and a lower cloud bill. The minimal storage savings from a snowflake schema rarely justify the performance penalty of additional joins in a cloud environment.

The market has validated this approach. The global Data Warehouse as a Service (DWaaS) market was valued at $8.11 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $39.58 billion by 2032. For more details, see the report on the growth of the DWaaS market. Platforms that thrive on star schemas can reduce deployment times by 70% and costs by 50% compared to legacy on-premise systems.

Modern Tools for Cloud Performance Tuning

Instead of focusing on normalization to save space, today’s data architects use a new set of tools available within cloud platforms to tune performance.

-

Clustering Keys: Platforms like Snowflake allow you to define clustering keys on large tables. This physically co-locates related data on storage, enabling the query engine to scan significantly less data to find what it needs. Clustering a large sales fact table by

OrderDatemakes queries filtered by a specific month extremely fast because the engine can prune entire micro-partitions. -

Partitioning: Similar to clustering, partitioning divides a large table into smaller segments based on a specified column, such as a date or region. When a query filters on the partition key, the platform performs “partition pruning,” intelligently ignoring all irrelevant partitions.

-

Materialized Views: These are pre-computed results of common, resource-intensive queries. If a key dashboard repeatedly runs a complex multi-table join, you can create a materialized view of that result. Subsequent queries then access the pre-computed table for a near-instant response, while the platform automatically handles keeping the view up-to-date in the background.

In the cloud, your primary modeling question shifts from “How can I store this data most efficiently?” to “How can I structure this data so it’s fastest to query?” This puts denormalization and query patterns at the center of your design.

Embracing the Lakehouse for Added Flexibility

The lakehouse architecture represents a further evolution, combining the low-cost, flexible storage of a data lake with the performance and transactional integrity of a data warehouse. This provides additional modeling flexibility.

With a lakehouse, you can ingest all raw data in its native format and then build structured, modeled layers directly on top of it within the same system. This architecture is a natural fit for modern ELT (Extract, Load, Transform) pipelines, where transformations are performed after data is loaded, leveraging the platform’s scalable compute power.

To understand this hybrid model better, see our guide on what is a lakehouse architecture. This approach enables a more agile and iterative modeling process, as analytical tables can be rebuilt or modified without reloading the raw source data.

Connecting Your Model to the Broader Data Ecosystem

A data warehouse model is the central hub connecting raw data sources to the BI tools that drive decisions. Its design dictates the structure of data pipelines, governance policies, and the long-term scalability of the entire analytics ecosystem.

A robust model must be designed not just for current requirements but also for future adaptability. The chosen structure is intrinsically linked to data movement and preparation processes.

The Critical Shift from ETL to ELT

For decades, the standard paradigm was ETL (Extract, Transform, Load). This involved extracting data from sources, transforming it on a separate processing server, and then loading the refined result into a structured warehouse. This rigid, schema-on-write approach required that all transformation logic be defined upfront.

Modern cloud platforms have enabled a more agile pattern: ELT (Extract, Load, Transform). In this model, raw, untransformed data is loaded first into the cloud warehouse or data lake. The platform’s own powerful compute engine is then used to perform transformations directly on the stored data.

This reordering of operations has profound implications for data warehouse modeling:

- Radical Flexibility: Modelers can experiment with different transformations without re-ingesting source data. The raw data remains available, allowing for the creation of new models, correction of errors, and ad-hoc analysis.

- Schema-on-Read: Instead of imposing a rigid structure before loading data, ELT allows the schema to be applied during the query phase. This is highly effective for handling semi-structured data formats like JSON and Avro.

- A Perfect Match for Data Vault: The Data Vault methodology aligns perfectly with the ELT paradigm. It is designed to ingest raw data into Hubs and Satellites first, with business logic and transformations applied later to create user-facing data marts.

This modern approach blurs the lines between data storage and processing. For more on this, see our data warehouse vs data lake comparison. Ultimately, ELT provides greater agility and control to data engineers and analysts.

Embedding Governance and Lineage Directly into Your Model

Effective data governance cannot be an afterthought; it must be integrated into the model from the outset. A well-designed model provides a clear, auditable trail of data movement and transformation, which is essential for regulatory compliance and building user trust.

A data model without lineage is a black box. You can see the final answer, but you have no way to prove how you got there. This is a non-starter for any serious data-driven organization.

Different modeling approaches offer distinct governance advantages. Data Vault, for example, inherently captures a complete, auditable history. Because its Satellites store every change to an attribute over time and are immutable, one can reconstruct the state of any business entity at any point in history.

Regardless of the methodology, strong governance can be embedded by:

- Using disciplined naming conventions for all tables and columns (e.g.,

Dim_Customer,Fact_Sales). - Adding descriptive comments and metadata to every object in the warehouse.

- Implementing Slowly Changing Dimensions (SCDs) to meticulously track historical changes to key attributes like a customer’s address or a product’s category.

Designing for Scale and Performance from Day One

A model must be built for growth. A design that performs well with 10 million rows may fail at 10 billion. Scalability is not a future problem; it is a day-one design consideration.

Modern cloud platforms like Snowflake or Databricks provide powerful tools for performance optimization, but the model must be structured to leverage them. Key techniques include:

- Partitioning: Physically dividing a massive table into smaller segments based on a key like

OrderDate. When a query filters on that date, the engine scans only the relevant partition(s), dramatically improving performance. - Clustering: Further organizing data within a partition. For example, clustering by

CustomerIDco-locates all of a customer’s records, speeding up queries that filter or join on that customer. - Incremental Loading: Designing data pipelines to process only new or changed records rather than performing full table reloads. This is critical for managing compute costs and ensuring data freshness.

By incorporating these techniques into your data warehouse modeling practice, you ensure the model is not just a static diagram but a high-performance, scalable asset for the organization.

A Practical Checklist for Data Warehouse Migration

Migrating a data warehouse is a complex strategic initiative, not just a technology swap. Success depends on meticulous planning, clear objectives, and a thorough understanding of the technical and business trade-offs. This checklist provides a roadmap for the process.

Begin with a comprehensive assessment of the current state. This includes not just the technology stack but every business process dependent on the existing warehouse. Document mission-critical reports, executive dashboards, and complex queries that inform daily operations. This inventory will serve as the benchmark for success.

Simultaneously, define the desired future state. Think beyond platform features and envision the analytical capabilities the business needs. Engage with stakeholders across the organization to identify requirements, such as real-time dashboards, integrated machine learning models, or self-service analytics that the legacy system cannot support.

Phase 1: Initial Planning and Vendor Evaluation

With a clear understanding of the starting point and destination, the next step is to select the right technology and partners. Vendor evaluation must go beyond marketing materials and focus on technical specifics.

- Technical Fit: Does the platform effectively support your chosen data warehouse modeling approach? Validate its performance with your specific schemas (e.g., star schemas) and its suitability for modern ELT pipelines.

- Ecosystem and Integration: Assess how easily the platform integrates with your existing tools, including BI software, data sources, and governance frameworks. Poor integration will hinder user adoption.

- Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): Do not focus solely on license fees. Model the full cost over three to five years, including storage, compute, data ingestion, and data egress fees. This provides a realistic long-term financial projection.

Choosing the right implementation partner is as critical as selecting the right platform. Look for a team with a proven track record of migrating systems of similar scale and complexity. Request detailed case studies and speak with references to verify their expertise.

Phase 2: Execution and Validation

The migration itself should be a phased, carefully managed process, not a single “big bang” event. Mitigate risk by breaking the project into manageable stages, such as migrating one business unit or data mart at a time. This iterative approach allows the team to refine the process with each cycle.

A phased migration builds momentum and demonstrates value early. It turns a monolithic, high-risk project into a series of manageable wins, which is crucial for maintaining stakeholder buy-in.

Post-migration data validation is the most critical task. Never assume the data is correct. Implement a robust validation plan that includes:

- Row Count Reconciliation: A simple but essential check to ensure record counts match between source and target tables.

- Metric Validation: Run key business reports on both the old and new systems. Core metrics, like sales revenue or customer counts, must align perfectly.

- Query Performance Benchmarking: Test critical and resource-intensive queries. The new platform must meet or exceed the performance of the legacy system.

Consistent communication is essential throughout the process. Maintain a regular cadence of updates for all stakeholders, be transparent about progress and challenges, and celebrate milestones to maintain momentum.

For a deeper dive into effective data movement, our guide on data integration best practices offers practical advice.

Common Data Warehouse Modeling Questions Answered

Here are practical, direct answers to common questions that arise during data warehouse modeling projects.

Star Schema or Snowflake Schema?

For most modern cloud data warehouses like Snowflake or Databricks, the default choice should be the star schema.

The reason is a pragmatic balance of simplicity and speed. The performance gains from fewer table joins and the ease of use for BI tools typically outweigh the marginal storage savings of a snowflake schema. Cloud platforms are optimized to execute queries efficiently on wide, denormalized tables.

The snowflake schema remains a valid option in specific scenarios, such as when dealing with very large dimension tables with highly repetitive attributes. In these cases, normalization can improve data integrity and simplify updates. For the vast majority of use cases, however, the performance trade-off is not worthwhile.

How Is Data Warehouse Modeling Different from Database Modeling?

This is a fundamental distinction. Traditional database modeling (often using Third Normal Form or 3NF) is optimized for online transaction processing (OLTP). Its primary goal is to eliminate data redundancy to ensure fast, reliable data writes and updates for applications like an e-commerce platform.

Data warehouse modeling is designed for analysis (OLAP), not transactions. It intentionally introduces controlled redundancy (denormalization) to structure data for one purpose: enabling fast and simple queries against large volumes of historical data. One is optimized for writing; the other is optimized for reading.

Can I Just Change My Data Model Later?

While technically possible, modifying a core data model is a complex, expensive, and disruptive process that should be avoided. The data model is the foundation upon which all dashboards, reports, and data pipelines are built.

Changes to a core fact or dimension table create a cascading effect, requiring updates to every dependent asset. This process is time-consuming and introduces significant risk.

This is why upfront design is so critical. It is also why methodologies like Data Vault have gained popularity; they are designed with inherent flexibility to accommodate evolving business rules and new data sources without requiring a complete architectural overhaul.

Choosing the right model is one half of the battle; choosing the right partner to help you build it is the other. At DataEngineeringCompanies.com, we’ve done the heavy lifting by providing independent, data-backed rankings of top data engineering firms. You can explore detailed company profiles, use our cost calculators, and find expert guidance at https://dataengineeringcompanies.com to make your decision with confidence.